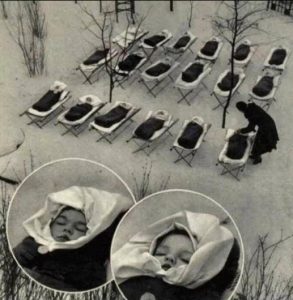

This photograph, taken in Moscow in 1958, provides a fascinating glimpse into a practice that was common in the Soviet Union and many other European countries during the mid-20th century. The scene depicted is both striking and unusual to contemporary viewers: rows of bundled-up infants sleeping peacefully on small cots in the open air, surrounded by snow. This practice, deeply rooted in the belief that exposure to fresh air and cold temperatures could bolster children’s immune systems, offers an intriguing intersection of cultural tradition, medical theory, and social policy.

The origins of this practice lie in the idea that fresh air is essential for good health, a belief that dates back centuries. By the early 20th century, this notion was widely embraced across Europe and the Soviet Union. Pediatricians and public health experts of the time advocated for the health benefits of outdoor exposure, suggesting that fresh air could prevent respiratory illnesses, strengthen the body’s defenses, and promote better sleep. In the Soviet Union, this approach was supported by state policies that emphasized collective well-being and preventive healthcare.

In the photograph, the babies are wrapped snugly in warm clothing and placed on cots arranged in neat rows. This level of organization reflects the Soviet emphasis on efficiency and order. Caretakers can be seen attending to the infants, ensuring their comfort and safety. The visual contrast between the snow-covered ground and the well-insulated babies encapsulates the central premise of the practice: that children, if properly dressed, can thrive even in cold weather conditions.

The belief in the health benefits of outdoor sleeping was not unique to the Soviet Union. Similar practices were observed in Scandinavian countries, where the harsh winters did not deter parents from letting their children nap outside. In fact, the tradition of outdoor napping for babies remains popular in countries like Finland, Sweden, and Denmark. Parents in these regions often park their babies’ strollers outside cafes, homes, or daycare centers, allowing them to sleep in the crisp air. Research conducted in these countries has suggested that outdoor naps can lead to longer, deeper sleep and may even reduce the risk of illnesses such as colds and flu.

In the Soviet context, however, the practice was more than a cultural tradition; it was a state-endorsed initiative. The Soviet Union placed a strong emphasis on public health and viewed the physical well-being of its citizens as integral to the strength of the state. This perspective was reflected in policies that promoted collective childcare, regular medical check-ups, and preventive measures. Outdoor napping was encouraged in state-run daycare centers and kindergartens, where children were exposed to the supposed benefits of fresh air from an early age.

The practice also aligned with broader Soviet ideals of resilience and hardiness. In a society that often celebrated endurance and self-discipline, the idea of exposing children to cold weather as a way to “toughen them up” resonated deeply. Parents and caregivers were encouraged to adopt routines that fostered physical robustness, and outdoor sleeping became a symbol of this approach.

Despite its widespread acceptance at the time, the practice of outdoor napping for infants was not without controversy. Critics questioned the scientific basis for the health claims associated with the practice and expressed concerns about potential risks, such as hypothermia or frostbite. However, proponents argued that as long as the babies were adequately dressed and monitored, the benefits far outweighed the risks. The thick layers of clothing and blankets visible in the photograph underscore the care taken to ensure the infants’ warmth and comfort.

From a modern perspective, the image invites reflection on how societal attitudes toward childcare and health have evolved. Today, many parents might balk at the idea of leaving their babies outside in freezing temperatures, even with proper precautions. Advances in medical science have provided new insights into infant care, and cultural norms around parenting have shifted significantly. The emphasis on outdoor napping in cold weather has largely diminished in many parts of the world, replaced by other health and wellness practices.

Nevertheless, the underlying principle of the practice—that exposure to fresh air is beneficial—remains relevant. Pediatricians today continue to recommend outdoor activities for children, emphasizing the importance of physical exercise and natural sunlight for overall health. In countries where outdoor napping traditions persist, parents often cite anecdotal evidence of improved sleep quality and fewer illnesses as reasons for continuing the practice. This enduring belief highlights the complex interplay between cultural tradition and scientific understanding.

The photograph also serves as a poignant reminder of the ways in which childcare practices are shaped by broader societal values and priorities. In the Soviet Union of the 1950s, collective well-being was a central tenet of governance. This ethos extended to childcare, with state-run institutions playing a prominent role in the upbringing of children. The outdoor napping practice exemplified this collective approach, with caregivers taking responsibility for the health and development of multiple children in a communal setting.

The scene captured in the photograph also raises questions about the lived experiences of the infants and their caregivers. What did a typical day look like for these children? How did the caregivers balance the demands of tending to multiple infants in such challenging conditions? And how did parents feel about entrusting their babies to state-run institutions that adhered to practices like outdoor napping? While these questions may not have definitive answers, they invite deeper exploration of the human stories behind the image.

In conclusion, the 1958 photograph from Moscow offers a window into a bygone era and a unique childcare practice rooted in cultural, scientific, and political contexts. The image captures not only a moment in time but also the values and beliefs that shaped the lives of countless children and their families. While the practice of outdoor napping for infants may no longer be as widespread, its legacy endures in the ongoing dialogue about how best to nurture and care for the youngest members of society. By examining such historical practices, we gain a richer understanding of the diverse approaches to parenting and health that have shaped human history.